Children were a visual rarity in Chinatown before 1900. Although the Exclusion Act exempted merchant families, according to the federal censuses, only two percent of Portland’s Chinese residents were children. Chinese merchant family histories indicate that having four to eight children was normal, but the census perpetually undercounted Chinese. Only after 1900 would Chinatown’s wives and children begin to appear in numbers in official records.

Founded in 1911 by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the School for Overseas Chinese offered Chinese language instruction to Portland Chinese youth by instructors from the new Republic of China. Along with language training, the teachers used history and culture lessons to instill Chinese pride and identity. Nearly all children growing up in Chinatown between 1911 and 1950 attended Chinese Language School every weeknight and Saturday morning for eight years or more. Their shared experience created enduring bonds during the last decades of Chinese Exclusion. Such language and heritage schools continue to be a fixture of Chinese American childhood across the country, particularly among the children of more recent immigrants.

Text from Beyond the Gate: A Tale of Portland’s Historic Chinatowns.

Patsy Fong Lee

Mary Nom Lee Leong

Norman Locke

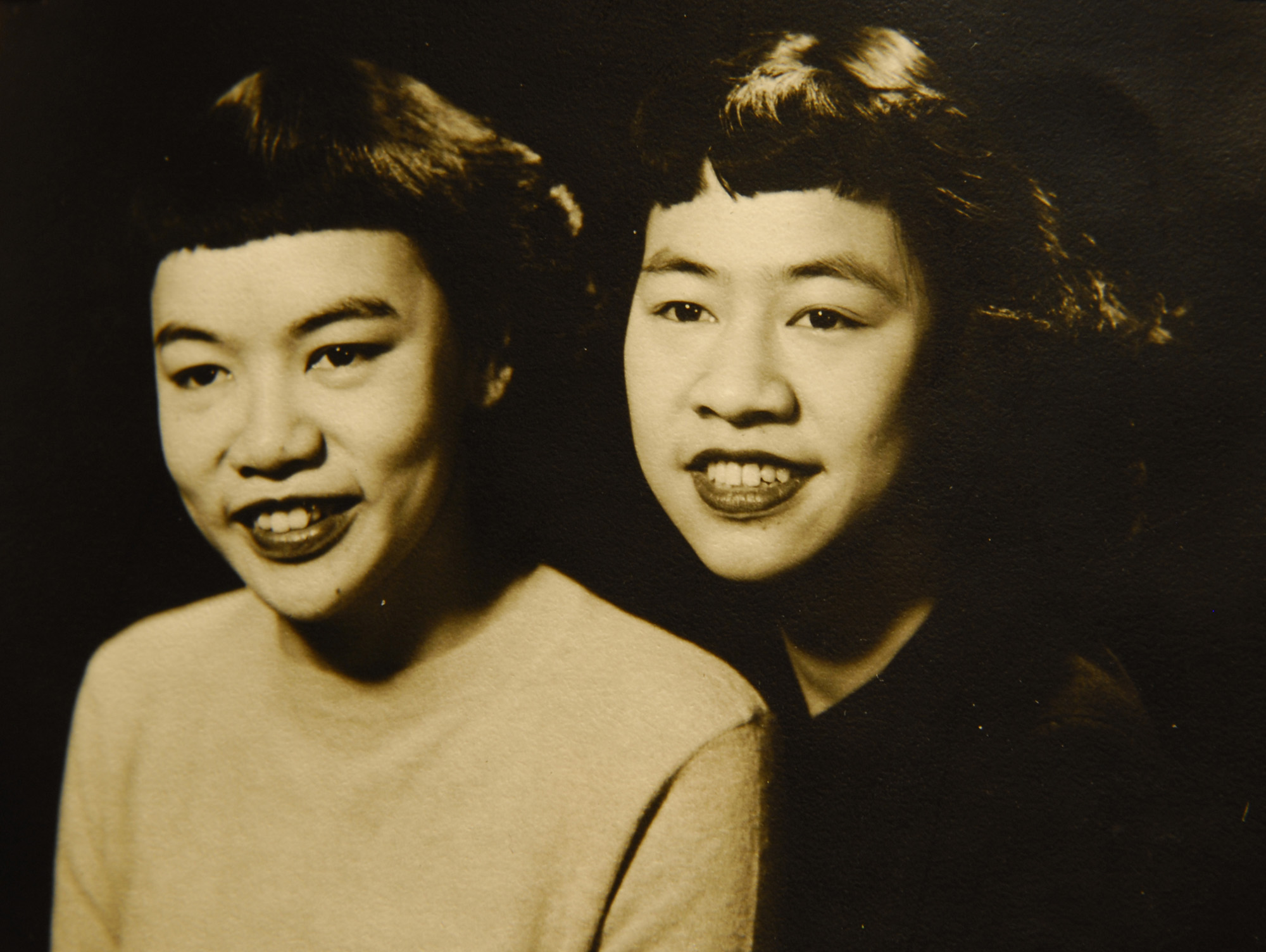

Top image: Mary Nom Lee Leong at age 15 with her friend Phyllis in Portland Chinatown, 1930s.

Slideshow images: photos courtesy of Patsy Fong Lee and family, the family of Mary Nom Lee Leong, and Norman Locke.